A lot of what I think about when looking at early-stage enterprise software companies is does this company have a chance to reach $1B in revenue at some point in their lifetime? While the revenue threshold to go public has historically been a fraction of that (though it’s continually increasing), a lot of the iconic companies that have persisted as durable public software businesses have hit that milestone en route to compounding beyond it.

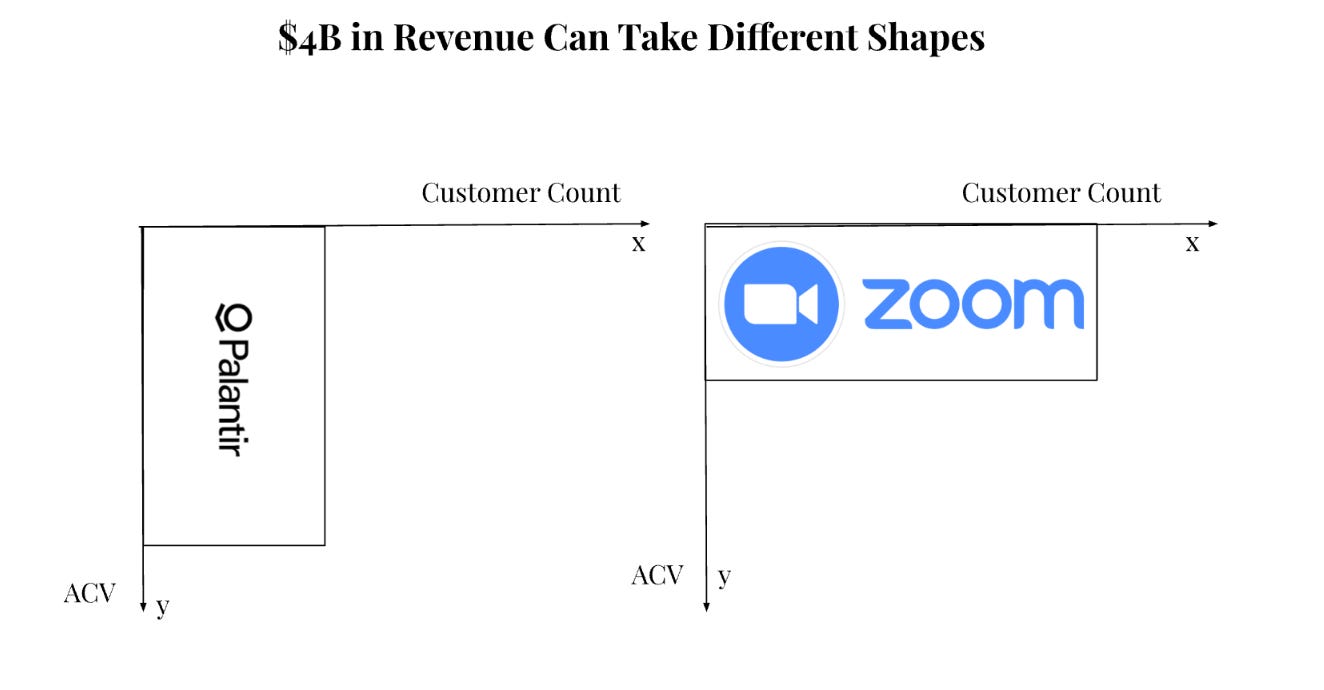

But when studying these software businesses, it’s immediately apparent that a certain revenue number can be achieved in a multitude of different ways. For example, take four public software companies that are all operating at roughly a $4B revenue run rate: Palantir, Snowflake, Crowdstrike, and Zoom. While the aggregate top-line for these companies are very similar, the breadth and depth of customer accounts that get them there are radically different:

Palantir serves 849 customers, with an average contract value of $4.7M

Snowflake serves ~11.6K customers, with an average contract value of $360K

Crowdstrike serves 74K customers, with an average contract value of $60K

Zoom has 478.5K customers, with an average contract value of $9K

The variance here is staggering! Zoom and Palantir (being both ends of the continuum) have coalesced at the same topline state in orthogonal ways: Palantir serves less than a thousand accounts, but has been able to create massive depth within each account. Zoom, on the other hand, has nearly 500K paying customers, but (on average) gets less than $10K from each customer annually.

Underlying this is two key observations:

Inherency of Tradeoffs: while any business would love to have the scale and ubiquity of Zoom with the account depth of Palantir, companies can’t have their cake and eat it too! Every business naturally has to make a decision on whether to tradeoff customer depth for scale or vice versa. It’s very rare for a public software company to have a “square” revenue shape of an identical customer count and ACV (though ZoomInfo does have this - 35K customers each paying them, on average, $35K).

The Tradeoff is Encoded in a Product’s Genes: different products naturally lend themselves to different adoption mechanisms, different GTM strategies, different ways of getting distribution, and different growth motions, with all of these coalescing into what I think of as a company’s shape of revenue.

For example, the Zoom product - a videoconferencing one - had product-led growth in its bones from the beginning. Being a product that everyone within an enterprise touches, with adoption not confined to any functional area, as well as a natural network effect that manifests when people have calls (within their organization or outside of it), a self-serve go-to market motion was the right bet. Zoom didn’t even have a marketing team for the first two years of the company’s existence, choosing instead to create a groundswell of new users with the combination of a freemium product and word-of-mouth distribution (similarly, Slack didn’t build an outside sales team until they hit $50M ARR and Canva didn’t build a sales organization until they passed $500M in ARR). Freemium by nature holds a tradeoff around breadth vs depth of accounts, with a company choosing to sacrifice immediate revenue for mass adoption, in the hopes that leading with scale combined with product magic can convert free users into paid ones over time. Naturally, product-led growth only works for a certain range of ACVs, because it thrives on a frictionless transaction being able to happen via the credit card of a non-decision maker in an enterprise. Zoom business being $18.33 a month? Unlikely that a CIO would have many objections to that (this pricepoint also expands the range of customers one can go after, bringing SMBs into the fold as well). A $2M software license? That begets the whole top down sales symphony: longer sales cycles, POCs, vendor bakeoffs, security and compliance checks, and often services engagements to deepen trust.

Services, on the other hand, are not only correlated with the ticket size of a given software product, but also the complexity of said piece of software. Professional services are inherently low gross margin for the software vendor– if companies can amass deployment across a wide base riding a perpetual wave of purely 70%+ margins, why wouldn’t they! There is a complexity threshold above which services is often needed, where a customer can’t be self-sufficient with the product in isolation and hence requires bespoke, high-touch support to render it valuable. This tends to be the case for deep, foundational enterprise platforms that require large scale migrations, implementations, integrations with existing systems, and customizations. Workday and Veeva are two examples of companies that won big following the use of services: at $60M of revenue, 46% of Workday’s revenue was professional services and 47% of Veeva’s revenue was professional services. Compare that to FY 2025, where ~90% of Workday’s $8.5B in revenue is product and 83% of Veeva’s $2.7B in revenue is product. Worth noting that Workday’s current revenue breakdown is 10.5K customers with a $758K ACV and Veeva’s is ~1.4K customers with a $2M ACV - there is a correlation between utilization of services early on and the steady state revenue shape of a company!

But if there’s one company that harnessed the learnings from services engagements into scalable product ARR better than anyone else, it’s Palantir. In fact, they did it so distinctively that they didn’t even call it services, they created their own term for it: forward deployed engineers. Forward deployed engineers are engineers who go to a customer site (these customers include government, defense, aerospace, manufacturing, healthcare, etc) and work with them, with the mandate not just to get software live and running, but to deliver real outcomes for that particular customer. A business purely composed of FDEs is more of a services company than a technology company; what made Palantir the latter rather than the former was the emergence of their software product Foundry (and the beautiful system that underpins it). While FDEs spend their time on purpose-built software for a given customer at hand, they funnel their learnings to another set of engineers known as PD (product development) engineers, whose main function is to build tools for the FDEs, automating parts of the work that are redundant such that FDEs have more leverage and hence can move faster.

There’s a feedback loop here. The learnings FDEs accumulate from the field serves as high-quality, customer-validated source material for the products built by PDs, with the tools PDs build enabling FDE efficiency such that the cycle can spin faster and faster. Over time, the work of the PDs became the productization of what the FDEs build, transforming isolated, one-off inventions into a coherent product with potential for scale. This is how Foundry came into being– its comparative distinctiveness in evolution is what supplies its edge, and why Palantir is able to consistently sell at deal-sizes in the 7 figures. It’s a hallmark of their unique business system: Palantir doesn’t just like to sell million dollar contracts, they need to sell those types of deals to be able to sustain the FDE model and absorb the costs that come with it.

Inherent within the Palantir business is a constraint on scale. The median enterprise software company sells to 10K customers, Palantir is only able to sell to a fraction of that pool. It’s not only because there are a finite number of FDEs that can set the system in motion, but because the number of customers that can absorb the ticket size (that’s needed to deliver the Palantir product) isn’t enormous. Zoom, on the other hand, is depth-constrained; while the product can amass a magical ubiquity in a viral fashion, the very thing that enables the explosive horizontal growth - frictionless adoption - constrains its vertical growth within accounts as well.

A good way to discern a company’s revenue shape is by asking the question: what is the defining constraint of a business, and what is the keystone tradeoff that forces it? It’s likely that the thing creating the constraint is core to an element that makes the business what it is, a property not of the product or market in isolation but of the integrated system that unites it all. Another interesting way to tease out (a hypothesis of) a company’s steady state revenue shape in the early days is by asking teams if their “low gross-margin subsidy of choice” to jumpstart usage is design partners and professional services or freemium subscriptions (and in the case of certain AI applications, seat-based pricing). How teams get their foot in the door of a given market contains a lot of signal around what their business will structurally look like in the fullness of time.

TAM Expansion

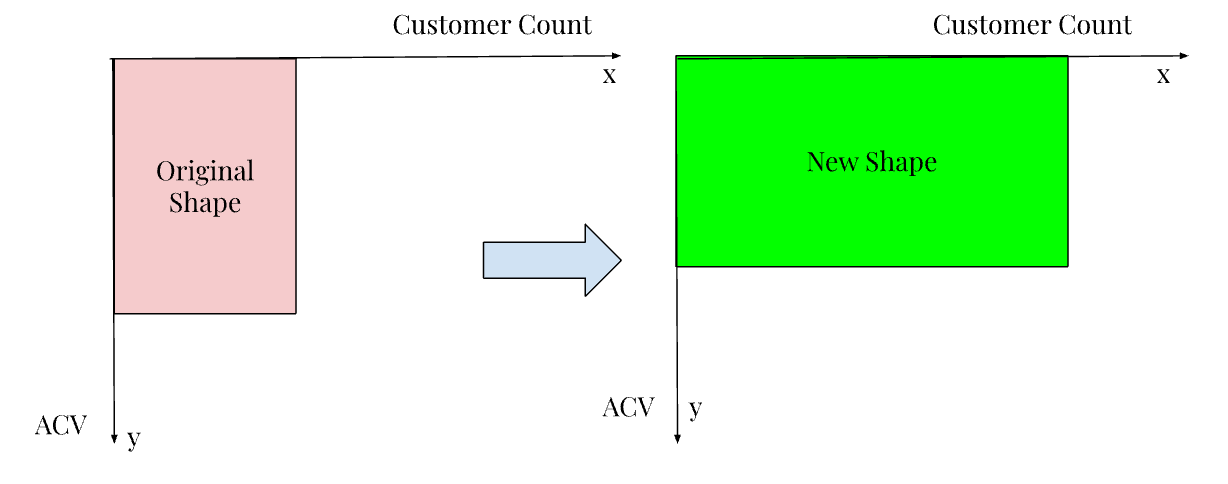

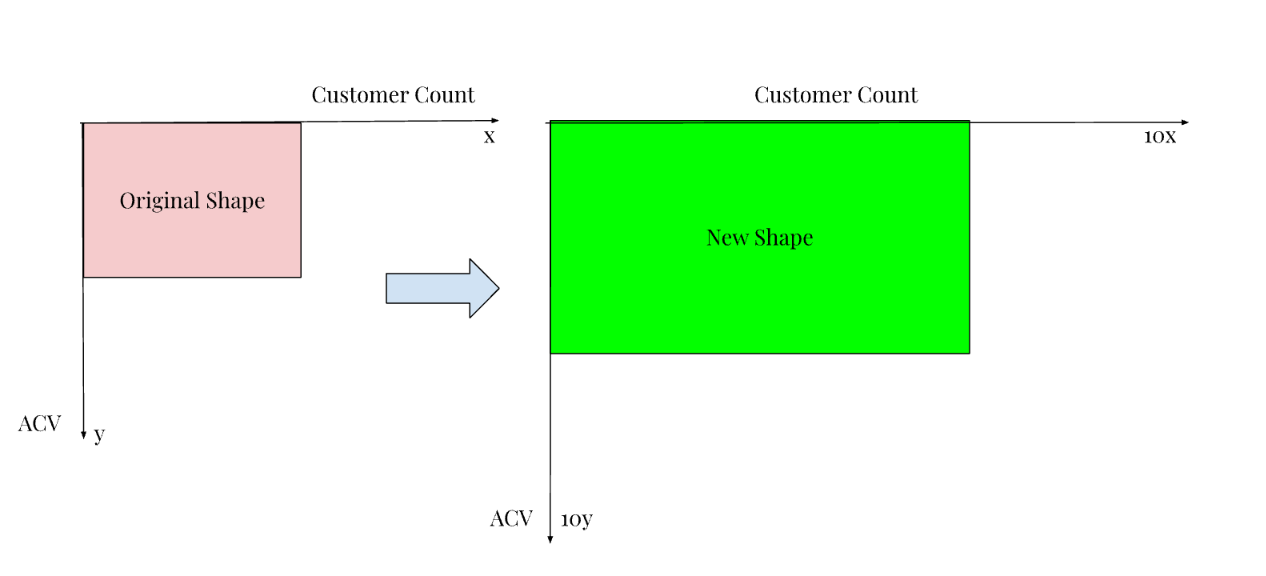

Especially in the midst of a secular shift in technology, the possibility of markets expanding rapidly thanks to newly created demand is top of mind for the entire ecosystem. This is something I think about often, and maps particularly well onto the idea of revenue shape: which shapes of revenue tend to benefit from which flavors of market tailwinds? Which revenue shapes are best positioned to catch which types of waves? The way I see it, there are two forms of market expansion:

Endogenous - Strictly Better Product Unlocks Consumption: a given product becomes cheaper, easier to use, and/or better such that buying the product becomes an economically rational transaction for a larger set of people. Snowflake unlocked consumption in the data warehouse market by making their product significantly more affordable and easier to run than Vertica’s, Netezza’s, and Teradata’s. New Relic and AppDynamics did the same with application monitoring (displacing on-prem incumbent Wiley). These shape evolutions tend to involve horizontal expansion. By definition, making something cheaper trades off account depth for account breadth. The hope is that a) a Jevon’s paradox like dynamic takes place (the cheaper per-unit costs and price elasticity creates more consumption, which paradoxically increases net spending / ACV) and b) teams can be intentional about their pricing strategy and multi-product roadmap such that they can upsell and cross-sell to compound within accounts (systems of record and usage based pricing lend themselves to this).

Exogenous - Tailwind Brings Net New Customers: this is when there is some outside force that expands the plane itself, bringing a set of net new buyers into the customer universe. While these step-function technology shifts implicitly influence endogenous market expansion by enabling a strictly better product to be built, their impact is felt explicitly here in ushering in a set of businesses that didn’t exist before. AWS, for example, enabled so many new developers to build businesses and get started quickly at a historically low level of friction, being an exogenous tailwind for a number of software infrastructure products that intersected with these developers early and rode the wave of their growth (think Stripe, GitHub, Mongo, Datadog, etc). Especially in these types of consumption-based pricing models where the ACV can be represented as a proportion of the customer’s top line (modeling IT spend as a % of revenue), products can enjoy massive amounts of ACV expansion by virtue of their customers doing well.

Shapes of Revenue in the AI Era

That’s why timing matters so much in company-building: the great companies get built when there are both forms of market expansion at play, combining to create outcomes that would have seemed unfathomable in years prior. Which is why it’s super interesting to see how this framework maps to what’s happening today in AI! Amidst a sea of unknown unknowns, what’s for certain is that both endogenous and exogenous market tailwinds are well in motion:

Endogenous: LLMs are enabling teams to create software products with cognition at the core, being fundamentally orthogonal to the platforms that preceded it. Given that the hallmark of these tools is doing a job, it naturally sparks comparisons to allocations of capital that filled in this input prior - services and labor. It’s likely that these AI-native application companies can expand the TAM for pockets of work that were inaccessible to many before, optimizing horizontally and enjoying the frictionless nature of Internet-enabled distribution.

Exogenous: the domino effect of AI innovation unlocking more AI innovation, in a self-perpetuating flywheel, will be astounding to see. The mental model I have for this is just as AWS lifted the constraint to access compute, AI tools do the same for accessing cognition. We’re already seeing the early innings of people using a stack of AI applications to move at a pace and create things they couldn’t have before. Case in point: Maor Shomo was able to, as a solo founder with no team, bootstrap his company Base44 to an $80M acquisition by Wiz in just 6 months. As more of these companies get started, coupled with the fact that they’ll likely be selling AI products that further perpetuate the cycle of enablement, there will invariably be a significantly larger base of businesses to sell to. Add in the possibility of the businesses who embrace AI to enjoy massive topline growth by simply doing more, and it’s likely that underlying AI businesses that power this will enjoy the fruits of ACV expansion.

So will the next crop of AI-native software companies, when at $4B in revenue, look more like Zoom or Palantir? While the horizontal market expansion argument may point to Zoom, it’s also worth noting that this generation of companies may mark a psychological shift in the way we think about certain application software businesses, going from selling tools that enable outcomes to selling outcomes themselves. As a company, the orientation is radically different if the SLA goes from being uptime and reliability based to being outcome based. For the companies that choose to deeply lean in and embrace this way of thinking as part of their bones (and not all will!), it’s very possible that they’ll have a shape that’s vertically-optimized. Their company operating system will likely include services engagements to build context on a customer, forward-deployed talent to enable deep embedding within existing enterprise workflows, and partner-esque support to make sure that the software not only works, but delivers. As Bret Taylor said on a recent appearance on the Acquired podcast:

“I also hope that if we fast forward 10 years and maybe we have the privilege of you're doing an Acquired on us and the magic of our business model is when you talk to our customers, we're the strategic advisor in AI. It's a deeper, more foundational relationship than simply a software vendor.”

The way I see it playing out: there will be certain companies, like Sierra, that embrace the strategic advisor approach and bake these partner-like habits into their genes. They’ll price on outcomes and build machinery that maximizes the proportion of product usage that nets said outcomes (because inherently, product usage that doesn’t create a desired outcome doesn’t get paid for and is negative gross margin). To enable this machinery, ticket sizes will be in the high range. The customers they’ll go after will be large scale enterprises that can absorb such a contract and willingly pay for it– financial services, media, retail, and others in the F500. Given the ambiguity of determining an outcome to price on, this will likely have to be bespoke for each customer, hence being downstream of real time spent within a customer’s universe (this is hard to scale horizontally!). Depth will be a binding constraint here, and these companies will have a revenue shape that looks like Palantir's, Workday’s, and ServiceNow’s.

And then there will be another class of businesses that follow the same theme that Cursor, Lovable, and Granola have been propagating (of the same family tree of Zoom, Slack, Canva, etc). Bottoms-up, product-led growth, with democratization of a certain task at the core of their business (with Cursor and Lovable its writing code, with Granola its note-taking). These products will be architected to spread like wildfire, with product flows that orient towards radically fast time-to-value and a “once you see it, you can’t unsee it” magical product experience that has users hooked from day one. ACV will expand as these products naturally self-navigate their way into the habits of users, but the pricing will be in service of potential mass ubiquity - not the other way around. Seat-based pricing has been the model so far but has created some unintended consequences with respect to power users; I really like Davis Treybig’s mental model of effort-based pricing that aligns with the compute used for a task and keeps gross-margin constant.

Obviously, these are two ends of a continuum, and there will be tons of companies that exist in the space between them (much like Crowdstrike and Snowflake today). Some companies may adopt a hybrid of seat-based, usage-based, and outcome-based pricing models. Some companies may apply services with certain customers and let self-serve work its magic with others. Flexibility is an asset to any early-stage team, with adaptability a necessity to react to market tides and follow demand coming from unforeseen places. But as these businesses mature, they will invariably face tradeoffs and constraints, which is the price paid for uniqueness. What matters most is leaning into it: being aware of their inherent revenue shape helps teams be more intentional about building the machinery (strategy, structure and organization design, processes, talent, company incentives, culture, capital allocation habits, etc) to manifest their full potential.

Credit goes to Meritech Analytics and software earnings calls for the public company data.